Black Sports Figures & Race

A century before Colin Kaepernick knelt down in protest against racial injustice, boxing champ Jack Johnson was flouting the racism of his day by cavorting openly with white women. Black athletes’ historic relationship with white America is complex and as varied as the sportsmen themselves.

Kaepernick’s symbolic gesture on the field wasn’t the first time African-American athletes made use of ceremonial moments to draw attention to their plight.

The 1968 Olympics in Mexico City saw gold and bronze medalists, Tommie Smith and John Carlos, respectively, take the honorary podium with raised fists and bowed heads after winning the 200-meter sprint.

Their “Black Power” salute during the National Anthem invited immediate rebuke from Olympic officials who regarded the act as an unwelcome political statement that ran counter to the spirit of the Games. Smith and Carlos were subsequently expelled from the competitions.

But it was renowned pugilist Muhammad Ali who generated a fiery media storm in 1966 when he refused to be drafted into the military. Having converted to Islam, Ali cited his religious beliefs, racial inequities at home and opposition to the war in Vietnam.

The controversial, trash-talking fighter consequently lost his boxing license and was stripped of his titles; they were reinstated four years later on appeal.

With a few exceptions, most prominent sports figures who reached celebrity status prior to the 1960’s Civil Rights era were less confrontational in public about race.

Jackie Robinson, the first black baseball player to join the major leagues in 1947, was a political independent with conservative views, including on the Vietnam war. He supported Richard Nixon’s 1960 presidential bid against JFK, though years later he would switch allegiance to the Democratic Party.

Carrying a different temperament than Ali, boxing icon Joe Louis volunteered to join the army in World War II despite the military’s segregated policy. His modesty and sportsmanship also won over the media and as a result, white America’s adulation.

“The Brown Bomber” became the first African-American to achieve a widespread hero status. In 1938, weeks before the highly anticipated rematch against Germany’s Max Schmeling, FDR invited Louis to the White House and remarked, “Joe, we need muscles like yours to beat Germany”.

Louis drew hard lessons from Jack Johnson’s experience as a boxer during the height of the Jim Crow racial laws. In 1910, after Johnson floored James Jeffries, dubbed “the great white hope”, riots broke out across the country as angry whites and jubilant blacks confronted each other.

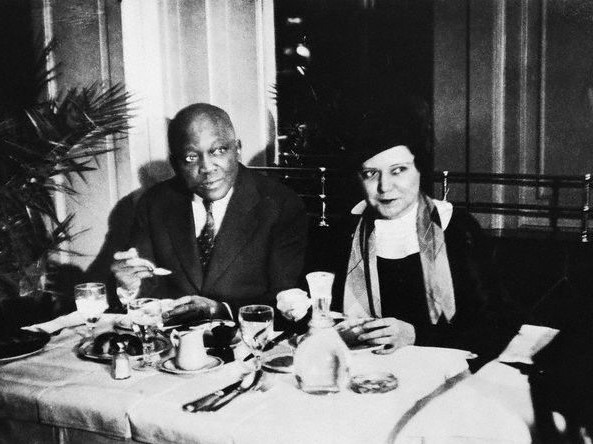

The world’s first black heavyweight champion, Johnson was an early example of a celebrity athlete but he was still widely disdained for beating whites in the ring and scowled for his inappropriate, flashy lifestyle. Defying the racial norms of the time, the Texas-born fighter openly dated white women and even married three of them (photo above with wife Irene).

Jesse Owens, the running star who defeated Hitler’s Aryan supermen at the 1936 Olympics, was aware of his second- class status at home but he was also preoccupied with making a living.

Owens joined the Republican Party and was paid to campaign against FDR at the 1936 presidential elections. In 1968, he refused to support the “Black Power” salute, stating that a black fist only has power if there is money inside. Years later, Owens would revise his opinion.

Personalities, economics and historical circumstances were all part of the complicated relationship between black athletes and their sports.