Return of the Wooden Tennis Racquet

A manufacturer and marketer team up to bring back the heritage

There’s a special quality in wood that evokes authenticity and timelessness. We find it in boats, toys, furniture, and for tennis enthusiasts in wooden racquets.

“Players enjoy the feel and sound of wood, the craftsmanship, and the aesthetic beauty of the timbers,” says Stephen Murphy, a former Seniors pro and founder of the Wood Tennis Club.

Based in Adelaide, Australia, Murphy teamed up with Grays International, a global sports manufacturer out of England, to bring back the vintage tool of the trade.

The idea came to him when he discovered by accident that Grays still had the ability to make wooden tennis racquets three decades after the implements became commercially obsolete.

Grays is the world’s oldest existing producer of wooden racquets and unlike other makers, the company didn’t discard the jigs and equipment they had used to fashion the old wooden frames.

“We actually first brought back the wooden racquets for Bjorn Borg’s unsuccessful comeback in 1991,” notes Richard Gray, CEO of the family enterprise that bears his name.

After retiring in 1984, the celebrated Swede returned to the professional men’s circuit starting with the 1991 Monte Carlo Open.

BUY- 'John McEnroe: But Seriously'

Borg grew his hair out again and stepped on the court with a personalized Grays wooden racquet. Facing Spain’s Jordi Arrese, he lost in 2 straight sets and failed to advance to the second round.

Borg couldn’t win a single set for the first 9 matches of his comeback. He was 35 years old, out of practice, and battling composite racquets that offered greater power and a deadlier spin.

But the romance of wood never left Grays, a leader in sporting equipment and premium wooden frames since 1855.

Based in Cambridge since its inception, Grays developed a tradition in making cricket bats, field hockey sticks, and lawn tennis racquets, building its reputation with University players.

Gray explains, “The racquets are handmade in Cambridge using tried and tested laminations of timber from a variety of English trees that we cut and process ourselves.”

BUY- 'Bjorn Borg and the Super-Swedes'

Early Grays tennis racquets were endorsed by stars such as Englishman Max Woosnam, gold medalist at the 1920 Olympics and champion at the 1921 Wimbledon doubles tournament.

While a student at Cambridge, the future King George VI was also a regular user of Grays racquets.

Today, Grays is more focused on making equipment, clothing, and protective gear for its internationally-recognized brands in cricket, rugby, and field hockey.

“Wooden racquets are a small but important part of the business and we continue to represent a tribute to the firm’s founder,” says the CEO.

The centuries-old use of wood in tennis racquets has a history in itself before it was replaced by aluminum, steel, fiberglass, boron, kevlar, and graphite.

As the primary weapon in a player’s tool box, the artifact traces its roots to the 16th century when an early form of the sport that resembled squash was played indoors in a walled court.

BUY- 'The Rivals: Chris Evert and Martina Navratilova'

At the time, the head was small relative to its handle and tilted in shape, allowing players to scoop low bouncing balls off the floor and walls.

As the game evolved into something more recognizable today, the head was enlarged and made symmetrical, the wood’s thickness was reduced, and the grip wrapped with leather.

One of the earliest improvements to the wooden structure, patented by Spalding in 1905, was a locked wedge that was inserted into the throat of the racquet to reinforce its weakest point.

In 1915, the Bancroft Company patented the 3-ply laminated racquet, which had a strip of leather sandwiched between 2 outer wooden layers, resulting in greater strength and flexibility.

By the 1930s, racquet construction included multiple thin layers that were bent cold and glued together under intense pressure. The innovation increased stability and decreased physical weight.

Writer and tennis historian, Richard Naughton, notes that Australia also had an influence on the story of wooden racquets because of the sport’s popularity in that country.

BUY- 'Billy Jean King: All In' (NYTimes Bestseller)

“Unlike in the U.S., most of the top amateur players during this period had some sort of link with the racquet companies, or sports manufacturers,” he points out.

Jack Crawford, outfitted by a Tasmanian racquet maker, made the flat top a popular design when he won his grand slams in the early 1930s, even though that shape was already deemed an antique.

Among other books, Naughton is the author of ‘Gentleman Jack: The Jack Crawford Story’ (Forward by Ken Rosewall) published by the Slattery Media Group.

Laminated racquets saw their heyday in the 1940s through 1960s, with some carrying as many as 18 layers of ply strips. Decorative paint, decals, and varnish catered to different consumer tastes and price-points.

By the late 1970s, composite racquets were making significant inroads among recreational players and professionals, promising improved aerodynamics and physical durability.

It spelled the death knell for well-known wood makers such as Donnay in Belgium and Bancroft in the U.S., both of which eventually disappeared as independent companies.

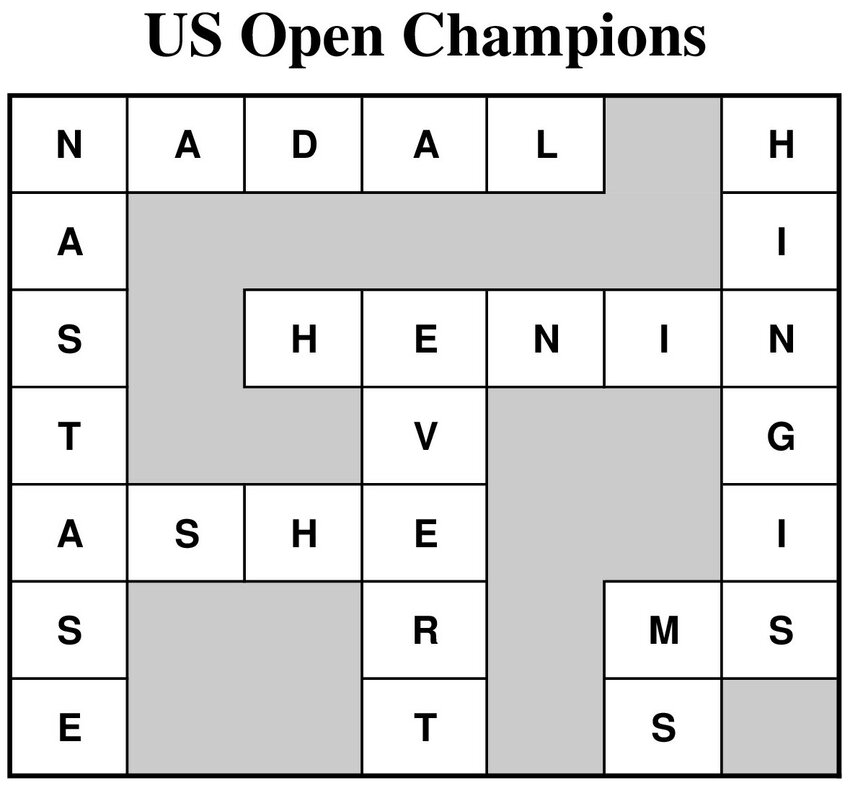

Some pros took their older implements as far as they could in competition. John McEnroe and Chris Evert won the US Open in 1980 and 1981, respectively, with laminated wood racquets.

In 2019, Murphy and Grays launched the ‘Masterpiece’, which they believe was the first commercially produced all-wood piece in over 30 years. The release featured a limited edition of 100 frames and sold out quickly.

BUY- 'Muscles: The Story of Ken Rosewall, Australia's Little Master of the Courts'

The ‘Masterpiece’ was followed in 2022 by the ‘Masterpiece International’, which has similar construction but different cosmetics, and ‘The Wingfield’, which pays homage to the ‘Father of Lawn Tennis’, Major Walter Wingfield.

This year, they came out with the ‘Mystique’, a racquet inspired by the model made for Borg at the time of his comeback.

All Grays racquets, which have been sold in 15 different countries, are strung in the UK by Paul Skipp, head stringer at Wimbledon.

Among Grays promoters and exhibitors are old-time pros such as Mikael Pernfors (finalist, 1986 French Open) and Fred Stolle (champion, 1965 French Open and 1966 US Open), who is also Wood Tennis Club’s ambassador.

Murphy isn’t under the illusion that today’s pros will pick up the wooden implements on the Tour, since their touch and feel create a different play from the modern game.

He wants to see wood tennis tournaments as a distinct form of the sport like beach tennis, or wheelchair tennis. This year, Murphy is organizing the first Australian Wood Tennis Championships to be held in November.

“I want to maintain the heritage of all-wood racquets and dismiss any notion that they need to be enhanced by other materials to be great racquets."

The price for Grays racquets starts at £205 (roughly $256) and they can be ordered by direct requests on the Facebook pages of Wood Tennis Club, or Grays Wood Tennis.

ENJOY OUR CONTENT? SIGN UP FOR OUR FREE WEEKLY NEWSLETTER AND SHARE ON YOUR SOCIAL MEDIA