Stickball, Death of a Street Culture

Keeping the game alive on Stickball Boulevard

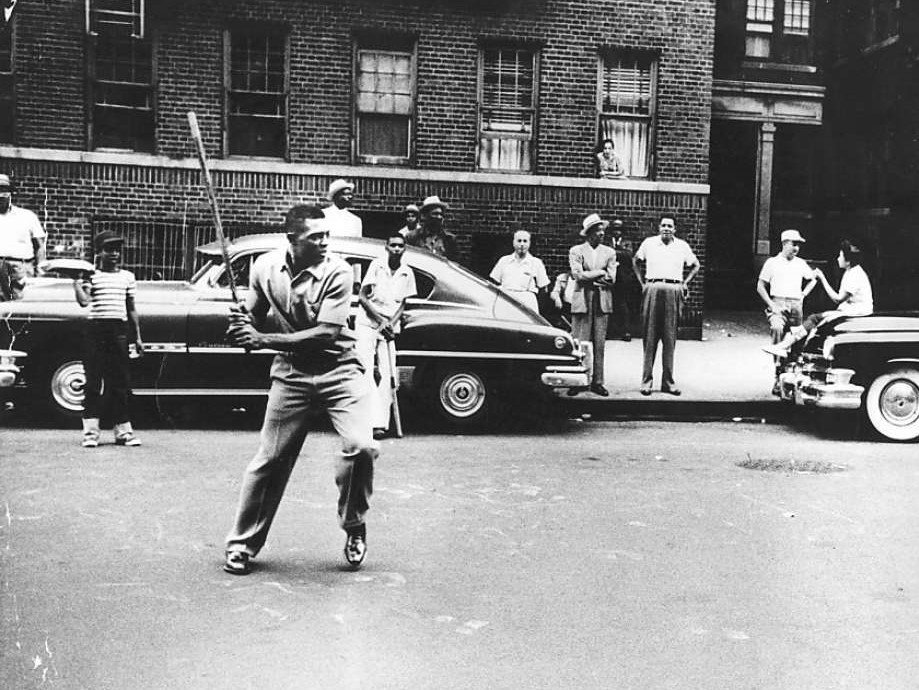

Like a modern Bruegel painting depicting kids in playful outdoor scenes, stickball was a familiar picture in America’s urban landscape during the mid-20th century. And like the Dutch painter’s subjects, it all but disappeared.

One corner in America where the game is still alive is on Stickball Boulevard in the South Bronx. In 1985, Newman Avenue was officially renamed after the street recreation that for generations was part of New York City’s social fabric.

BUY- Willie Mays 1969 Topps trading card

“The Mecca of stickball is in the South Bronx”, says Jennifer Lippold, former President of the New York Emperors Stickball League. “It’s where you go for bragging rights.” She now runs the kid program, which takes place alongside the amateur adult league every Sunday between April and August.

Lippold’s father was a founding member of the Emperors, an organized league that got going in the mid-1980s as a way to settle differences among kids and between neighborhoods. Today, the adult league boasts 10 teams, which include seniors whose passion for the game keeps them coming back every weekend during the summer.

Back in the day before “stranger-danger” became embedded in parental consciousness, youngsters living in cramped apartments in northeast cities like New York, Philadelphia and Boston made the streets their playground.

Hopscotch, handball and tag all had their street variations, which in many cases originated in old Europe and brought over by immigrants. But no pavement activity was more quintessential American than stickball, a variant of baseball with its own street rules.

Until the late 1950s, baseball-crazed New York had three professional teams: the Yankees, Dodgers and Giants. Football and basketball, while popular in college, were still in the shadow of America’s favorite pastime and didn’t produce the same iconic sports heroes.

For impoverished and lower-middle class teenage slickers, stickball made the most with the least. A broom stick passing off as a bat and a high-bouncing spalding ball were enough to launch pick-up games and create neighborhood teams. There was no need for expensive equipment such as gloves, spikes, or uniforms and every neighborhood became its own franchise.

Manhole covers were used as home plate, fire hydrants and parked cars as bases, buildings as foul lines. There was fast pitch against a wall with a chalked strike zone, slow pitch with a bounce, and the ubiquitous self-tossing fungo.

Dashed Hopes for the Havana Sugar Kings

Tossing and swinging while the ball was still in midair didn’t carry the same grit machismo as letting it first bounce on the asphalt and then taking a swat. “In the Bronx, they use the bounce toss but in Manhattan it’s still the pitch”, chuckles Lippold. Urban sluggers who could hit the ball two or three “sewers” down the block became neighborhood legends.

In more confined spaces like back alleys and side streets, singles, doubles and triples were determined by where the ball hit. Landing a spalding on a building roof was either a home run or an out, depending on preset verbal agreements.

Rules varied from neighborhood to neighborhood, city to city, but with one common feature- a freewheeling playing spirit and the absence of supervision. While today on Stickball Boulevard kids show up with their parents, the elder supervision doubles as a way to pass down a game they grew up on.

Legendary All-Star Willie Mays learned to hit breaking balls on the streets of Harlem during his first two years with the Giants, swinging mop sticks between parked cars without coaches or trainers. More recently, retired Yankees pitcher, CC Sabathia, was just one of the baseball celebrities who showed up on a Sunday at Stickball Boulevard to help raise interest in the game.

Stickball contributed to a vibrant street life, but not everyone relished play time. For some residents, shattered windows and neighborhood interruptions were too much. Building superintendents and cops driving by confiscated balls and broke sticks. In many instances, they dropped the brooms down sewer holes, instantly ending a game.

In 2006, documentarian Sonia Gonzalez-Martinez released a short film called “Stickball: Bragging Stories”. Old timers are interviewed about their memories growing up with the game, revealing colorful urban tales and the ethnic mosaic of city life.

Italians, Puerto Ricans, Irish, and African-Americans had their own teams, mirroring their respective neighborhoods. On normal days, they risked street fights if they ventured into each others’ turfs, but when a stickball match was scheduled there was free pass. The only caveat was that as soon as the game ended, the visiting team had minutes to clear the neighborhood, or the civil gathering would turn violent.

At Home with the Louisville Slugger

Once car traffic started growing in cities, stickball found a home in school yards and open lots. The king of street games still remained popular but would suffer a slow death with shifting cultural patterns and the advent of more recreational options.

The 1980s ushered in video games and cable TV, resulting in youngsters spending more of their leisure time indoors. Overprotective parents also turned sports into organized and sanitized activities, controlling everything from playdates to transportation.

Branded superstars like Michael Jordan drew interest towards pickup basketball games, while new diversions like skateboarding made different use of the streets.

One of the Emperors’ missions today is to get kids out of the house and away from sedentary activities. If parents and even grandparent can connect with family members on a multi-generational level, then it makes the effort that much easier and more enjoyable for everyone.

The Emperors aren’t the only league that still play stickball. Teams are active in California and Florida and a few times a year they hold tournaments. Still, when it comes to stickball culture, the streets in the South Bronx remain the closest we have to those long-gone days of yesteryear.

ENJOY OUR CONTENT? SIGN UP TO OUR FREE WEEKLY NEWSLETTER AND SHARE WITH YOUR SOCIAL MEDIA FRIENDS.